Originally published in Myth & Mayhem | June 22, 2020

“What are we calling postmodernity? I’m not up to date.”[1]

— Michel Foucault

Postmodernism, a Problem of the Left or the Right?

In his popular self-help book 12 Rules for Life and on his personal website, psychologist Jordan Peterson argues that the “postmodernist left” has created a culture where all truth and morality is relative. Blaming the “dominance of postmodern Marxist rhetoric in the academy,” Peterson claims that political correctness and hostility towards men are the results of this so-called postmodernism.[2] Peterson is not, of course, the first to accuse the left of promoting a postmodern agenda. In the 1980s, classicist Allan Bloom feared that left-leaning professors filled young minds “with a jargon derived from the despair of European thinkers, gaily repackaged for American consumption and presented as the foundation for a pluralistic society.”[3] Following suit, conservative pundit Roger Kimball wrote that college students had become “committed to an ethic of cultural relativism,” and that “in order to realize the freedom that postmodernism promises, culture must be transformed into a field of arbitrary options.”[4]

Even though conservatives characterized postmodernism as a problem with the left, the rise of “fake news” and media spectacle associated with Donald Trump caused left-leaning thinkers to depict postmodernism as a problem with the right. Literary critic Jeet Heer called Trump “America’s First Postmodern President,” saying that the president “is the product not just of a fluke election or a racist and sexist backlash, but the culmination of late capitalism.”[5] Journalist Ryan Cooper argued that the politics of the right represented “a load of cynical gobbledygook,” and that “if there is any political faction that behaves like the most hysterically exaggerated caricature of postmodernism, it is the current Republican Party.”[6]

That both sides of the political spectrum blame postmodernism for society’s ills points to an issue of definition. Postmodernism is not so much a problem of the left or the right, but rather, the problem lies in its vague terminology and the common theoretical misunderstandings associated with it. In other words, when the left or the right speaks of postmodernism, they usually mean different things. Postmodernism is better understood as an umbrella term that houses a wide range of political, economic, and aesthetic ideas under it. To get to the heart of postmodernism’s consequences, it is first necessary to take a step back and determine what postmodernism actually is.

Postmodernism and Its Relationship to Modernism

As its name suggests, postmodernism is often considered the era that comes after modernism. Like postmodernism, modernism is a broad category that contains a collection of twentieth-century ideas, and it is replete with its own contradictions and varying perspectives. In some ways, postmodernism is a reaction against modernism, yet in other ways, postmodernism is an extension of it.

Put simply, modernism refers to a collection of philosophies and artistic movements that sprouted up in response to the horrors of World War I.[7] Its origins, however, go back a little earlier to the end of the nineteenth century when some key figures uprooted long-held paradigms. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution is arguably the first major influence on modernist thought, as it demonstrated that humans were not divinely created, but were instead the product of a larger biological and ecological system.[8] Fascinated by Darwin’s assertion that nature was dynamic, Friedrich Nietzsche contemplated the spiritual and philosophical consequences of such a world, and he concluded that the history of philosophy from Plato through Hegel had to be reconsidered when faced with the newfound reality of evolution.[9] Similarly, Karl Marx criticized the idealist notions that dominated philosophy at the time and instead used Darwin’s concepts as the scientific basis for his materialist approach to history.[10] And, also like Darwin, Sigmund Freud asserted that human action is shaped more by one’s environment and subconscious fears and desires rather than one’s conscious, rational thought as the Enlightenment philosophers had declared.[11]

These four evangelists of modernism did not agree on everything, of course, but what is important about them collectively is that they all influenced modernist thought by displacing the enduring myths of the old world with modern ideas. The modern world was now one that could no longer depend on the institutions of the past (the Church, the State, the Individual), but one that could be explained in terms of a system (natural selection, the will to power, class struggle, the unconscious). Hence, at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, artists and writers rejected tradition (as tradition was no longer justified) and embraced Ezra Pound’s modernist adage to “make it new.”[12] As such, artists created impressionistic and surrealistic works, writers used a stream-of-consciousness technique, and composers broke free from standard tonality.[13] But modernism was not just a change in style but a change in theme. As the most devastating conflict in human history up to that point (in part due to advanced military weaponry), World War I left many searching for larger truths but also skeptical about science and notions of progress.[14] So the modernists simultaneously tried to explain the world through grand narratives, but they were also painfully aware of their limitations in doing so. It is in this tension that the key themes of modernism become apparent: a quest for universal truth or morality, a desire for clear-cut identities, a penchant for seriousness and distinctions between “high” and “low” culture, and an uneasy relationship with technology.[15]

By the end of World War II, most modernist movements had either faded away or evolved into different forms. The world had now become global, and the rise of mass media ushered in the age of mass culture. The amalgam of the mass media and the advertising industry dominated the postwar era, leading to a homogenization of culture propagated by what Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer termed the “culture industry.” These Frankfurt School theorists saw a real danger in the collapsing of serious art into marketable and easily digestible entertainment products not because they were elitists (as they are so often maligned), but because the culture industry posed a threat to both intellectual development and revolutionary potential. In other words, the culture industry pumps out cheap forms of entertainment intended to stimulate consumerism and pacify consumers so they will not rise up against the capitalist system.[16]

The Frankfurt School theorists formed the field of study known as “critical theory,” which figures like Peterson incorrectly conflate with postmodern thought because of its focus on culture and power. But this error demonstrates a lack of understanding about the relationship between modernism and postmodernism. The critical theorists fit squarely into modernist thought: generally speaking, they combined Marxism and Freudianism, and their analyses of modernity are best seen as early criticisms of the postmodern world developing in front of them. Further, their analyses stemmed from a structuralist perspective, in the broadest sense of the term. Structuralism contends that human experience can be analyzed according to its relationship with an overarching structure. This relationship can be materialist (as in Marxism), symbolic or mythological (as in anthropology), linguistic, psychological, and so on.[17] While structuralist approaches can vary, the main takeaway in this context is that they all rest on the notion that one can objectively analyze a coherent system. Postmodernist approaches, however, would break away from this framework and instead question the possibility or limitations of analyzing a system when one resides within it.

It is at this crossroads where modernism and postmodernism begin to inhabit distinct spheres. But “postmodernism” as an idea would only get more complicated. To properly define it, postmodernism must be divided into three different but related concepts: postmodernism as an aesthetic movement, postmodernism as a linguistic challenge, and postmodernism as a societal analysis and critique.

Aesthetic Postmodernism

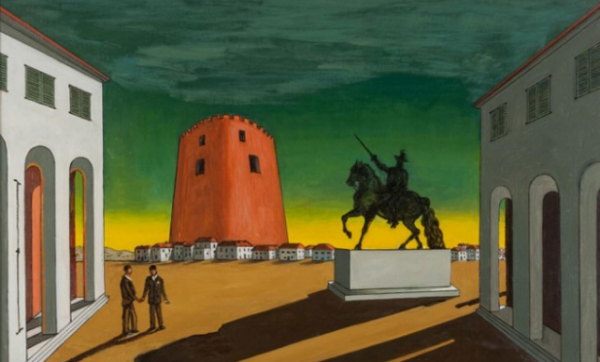

Aesthetic postmodernism is perhaps the easiest concept to grasp because one simply need compare modern art to postmodern art to see the distinctions between them.[18] In some ways, they are similar. For instance, modernist artists embraced the avant-garde as part of a wholesale rejection of the artistic standards of the past. In that sense, postmodern art, too, could be seen as a rejection of traditional standards. But there are key substantive differences that go beyond simply a rejection of tradition.

The modernists viewed their art as radical reflections on psychology or politics. The seriousness of their position was illustrated in the many manifestos that accompanied their artistic movements, such as the Surrealist Manifesto or the Dada Manifesto.[19] In literature, writers filled their pages with allusions to the classics, requiring one to have an in-depth knowledge of every major work that came before it in order to grasp the work’s deeper meaning.[20] In music, modern compositions often pushed the limits of traditional tonal harmony or even abandoned it completely, exploring the possibilities of atonality. Such compositions may sound weird or even nonsensical to the untrained ear, but they are anything but: modernist composers took music to its utmost intellectual level. The point here is that the modernists took the separation between high art and low art quite seriously, whereas postmodern art would instead collapse the division between these two domains.[21]

Postmodern art, then, embraced the playful, the absurd, the superficial.[22] In this new postwar world dominated by the culture industry and mass media, the separation between high and low art became blurred. Rather than taking the serious tone of modernist art, postmodern art made frequent references to high culture by reducing it to a mere image to be parodied. The most recognized example of this is the art of Andy Warhol, who created facsimiles of mass-produced products and celebrities and presented them as gallery-worthy art pieces. But this kind of parody lacked a substantive critique. Warhol supposedly said that art is merely “what you can get away with” and that he is “a deeply superficial person.”[23] Serious parody or satire has something to say about society—postmodern art rarely does, and instead, it often celebrates superficiality. This lack of a societal critique turned parody into a shallow, detached pastiche. Frederic Jameson noted that pastiche was a kind of “blank irony,” a “neutral practice of such mimicry, without any of parody’s ulterior motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of laughter and of any conviction.”[24]

This empty art form did not arise in isolation, however. Rather, it was the aesthetic of a world that had become dominated by advertising and consumerism. Jameson argued that “every position on postmodernism in culture—whether apologia or stigmatization—is also at one and the same time, and necessarily, an implicitly or explicitly political stance on the nature of multinational capitalism today.”[25] Simply put, postmodern art could be seen as both a product of and an acquiesce to capitalist society.

This phenomenon led Arthur Danto to pen his oft-cited essay “The End of Art,” in which he argued that contemporary art forms were no longer constrained by the aesthetic standards of the last few centuries of art history—that art was no longer wedded to mimesis or ideology, but had reached a new historical moment where anything goes, saying that “all there is at the end is theory, art having finally become vaporized in a dazzle of pure thought about itself, and remaining, as it were, solely as the object of its own theoretical consciousness.”[26]

While modernist movements like Dada or Marcel Duchamp’s readymades were clearly predecessors to postmodern tendencies, they were still movements in themselves. After modernism, there were no more “-isms.” Art did not have to reference art that came before, but could be entirely self-referential, in a kind of aesthetic free-for-all. Art could be kitsch or performance or even advertisement. That is not to say that art is not still being made, but rather, art, like Danto explained, became free from any required connections to historicized movements. Thus, postmodern art is—in the simplest terms—art that came after the modern period and collapsed any pretense of prescribed meaning as a necessary precondition. Like Bubble said to Patsy on Absolutely Fabulous: “The photocopier is running out of ink. You’ve been roneoed and roneoed over and over, and this is the very last copy.”[27]

Linguistic Postmodernism

While postmodernism in its artistic context is a bit easier to grasp, linguistic postmodernism is harder to conceptualize, which is, ironically, one of its main points. This form of postmodern thought stems from the “cultural turn,” a shift in academic thought that focused more on meaning, especially within language.[28] These debates centered around challenges that poststructuralism posed to structuralism. The linguistic structuralists saw culture as a closed system, where language could be understood in relation to the broader structure in which it resides. The poststructuralists, however, questioned whether that very language is reliable enough to describe the real world.[29]

Since language is a human creation, it is naturally riddled with human biases and flaws, which can cause errors in communication. For instance, if one says the word “home,” a plethora of images come up in one’s mind depending on their own subjective experiences. A “home” could mean many types of buildings, or it could conjure images from one’s childhood, or it could refer to one’s nation, and so forth. To understand what meaning is intended, the word must be seen in context to other words around it, yet those words also fall victim to the same misunderstandings. And this example is merely a simple one: imagine how complicated meaning becomes with abstract words like “justice” or “freedom.” The point here is that the structuralists tried to understand language and culture by exploring these relationships, whereas the poststructuralists viewed the larger structure as its own problem.

Language’s susceptibility to miscommunication led Jacques Derrida to consider a new way to analyze ideas, which he called “deconstruction.” Put simply, deconstructing an idea means to sniff out its inherent contradictions.[30] As a lover of art and music, Derrida felt that certain important human ideas could not be captured in words. Everyone has likely had this same experience: sometimes a painting or a musical composition evokes feelings and thoughts that cannot be expressed in regular language. He felt that the human tendency to always want ideas to have straightforward meanings illustrated an immaturity in intellectual development. For instance, the structuralists considered the meanings of words by evaluating their opposites. But Derrida would argue that there is something to be learned from the internal conflicts of opposite terms. Hence, Derrida advocated for aporia, a kind of intellectual state of maturity wherein humans have made peace with the fact that life’s answers are not always clear.[31]

This approach should inform one’s reading of a text, such as a work of art or literature. A structuralist might interpret a text by determining what the author or artist intended, which is, of course, a great place to start. But Derrida famously stated that “there is no outside text” (often misquoted as “there is nothing outside the text”), meaning that the text absorbs all kinds of meanings within it, and the person analyzing the work should take into account other information that might inform one’s understanding of it.[32] For example, while Jane Austen may have intended a particular social or political critique in her novels, a reader of her work should also take into account her role as a woman in English society, the class nature of the landed gentry in the eighteenth century, the significance of etiquette rules at the time, and so on. Deconstructing a text does not mean that all interpretations are equally valid, but it does allow for more nuance by analyzing ideas within their historical and linguistic context. For Derrida, the words on the page should not necessarily be taken at face value—one must read beyond the actual words and beyond the author’s intent to find hidden truths, and those truths are likely not static. Put another way: deconstruction makes one open to meanings and subtexts that may lurk beneath the surface of the language being presented.

But these linguistic concerns did not just apply to analyzing cultural texts, but to society as well. Like Derrida, Michel Foucault addressed the problems of language, but he was especially interested in the relationship between language and power. For Foucault, humans use language to construct their knowledge of the world, but that process creates a “discourse” that confines human experience inside it. In other words, language creates a kind of construct, where any attempt to explain the world outside of that discourse is difficult, if not impossible, because the very ways of explaining are already wrapped up in the discourse itself.[33] And if that is not problem enough, these systems of thought can produce their own power structures.

Take sexuality, for instance. Cultures have responded to homosexuality differently throughout history, but when the actual term “homosexual” came into use during the nineteenth century, a discourse developed around the concept of homosexuality, which Western medicine could then scrutinize and normalize. This term came to encapsulate a set of standards about acceptable or non-acceptable behaviors that still dominates the way people discuss sexuality today. The same can be said about the concept of madness. Societies have always had ways of dealing with those who fall outside the norms of behavior, but with the development of the Enlightenment-era idea of “insanity,” those who seek to identify and institutionalize these behaviors can do so from a position of power that is created by the language itself. Put another way: the very fact that this language exists to describe a certain type of person automatically creates an uneven power dynamic between he who diagnoses versus he who is diagnosed, or, as Foucault puts it, “dominant knowledges impart power to those who know and speak them.”[34] The development of this discourse, then, is not a reflection of power that exists before the creation of the discourse, but a reflection of how power is produced linguistically. Thus, Foucault would argue that the insane person does not exist outside of the discourse, but rather, society constructs the insane person through language.

This insight clearly has real-world consequences as it demonstrates that language itself can produce power. How is one to determine the nature of reality when one’s entire knowledge of the world is made up of these discourses? In other words, how can one objectively analyze a bubble when they reside inside that bubble? Both Derrida and Foucault’s ideas have been grossly oversimplified by both the left and the right as just pure relativistic or pluralistic jargon. But those caricatures unfairly downplay the challenges they each present.

Societal Postmodernism

While some postmodern theorists focused on linguistic concerns, others tackled the uniquely contemporary problems of late capitalism. By the 1970s, the roots of neoliberalism had begun to take hold, and by the end of the twentieth century, global corporate power had supplanted much of the authority of national governments. At the same time, industrialized countries underwent a digital revolution, which would drastically increase communicative ability, especially with the development of the web. This amalgam of factors led to the world of today—a world that is dominated by unprecedented access to information, 24-hour news cycles, social media, and non-stop advertising.

In this post-industrial society, knowledge production has become commodified, which means that it is no longer subject to rigorous standards, but to capitalism’s whims.[35] Take for example television news, which is formatted to appeal to consumers, so it only focuses on what is sensational rather than what is substantive or relevant. TV news is not primarily intended to inform or to enrich, but to entertain. Neil Postman argued that television is “altering the meaning of being informed by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation,” which he explained was “misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information, information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing.”[36] Jean-François Lyotard saw the rise of this postmodern age where the “legitimation of knowledge” is subject to markets rather than objectivity, and the modernist “grand narrative has lost its credibility” because knowledge was no longer subject to truth but to conflicting metanarratives.[37]

These theorists pointed to a problem unique to late capitalism, where people have become inundated with information and images that have completely changed the way knowledge is produced, consumed, and processed. For most of human history, a key problem in understanding the world was a lack of information. But in this postmodern age, too much information has become a problem. And to exacerbate things, much of the information is tied to advertising. Now, the average person sees about 5000 ads per day.[38] Being bombarded by non-stop images and information means that regular people have neither the time nor the mental capacity to sort and consider all this information for credibility or significance in any meaningful way, so they become passive absorbers rather than analyzers, or, as Jean Baudrillard put it, humans have become “a pure screen, a pure absorption and re-absorption surface of the influent networks.”[39]

The consequences of this new world are multifaceted. In his commonly misunderstood essay, “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place,” Baudrillard points to the way that one’s interpretations of world events are skewed by media’s use of propagandistic imagery. The viewer of Western, corporate-owned, imperialist-aligned media only sees the selective and stylized portrayals of violence that the viewer is completely disconnected from, and thus develops not only a biased perspective but one that hardly represents anything close to reality.[40] To make matters worse, as digital technology improves, it can render simulations that seem more and more realistic, to the point that simulations of reality start to seem more real than reality itself, what Baudrillard referred to as the “hyperreal.”[41]

Baudrillard’s notion of the hyperreal essentially predicted the internet culture of today. The hyperreal is so similar to the virtual world that the creators of The Matrix based the idea for the film on Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation and made it required reading for the actors.[42] Baudrillard would later explain, however, that, in the film, there is a clear delineation between the real world and the virtual one, whereas in a hyperreal world, those lines have blurred and one cannot tell the difference between the two.[43] A better example of his concept would be influencers on Instagram, a group of people designed to sell lifestyle products by fabricating a reality—the lifestyles themselves—that simply does not exist, one where everyone is beautiful, rich, happy, and fulfilled.

The influencer example is just one piece of a bigger picture about advertising and capitalism in the postmodern world. Influencers describe their very being as a “brand.” Let that sink in: the lifestyles they project—their entire identities—are projected in terms of commodities. And this phenomenon points to a distinctiveness about the postmodern condition: commodities are no longer just objects (labor plus a material substance), but are also ideas, images—signs. A commodity’s value is now determined in the abstract, not by evaluating the labor or the actual material, as both classical and Marxian economics do. Instead, a commodity today is more likely to have value by projecting the appearance of status. Take for example a luxury clothing line. It is likely the case that the actual quality of the clothes is the same as a generic brand, and the amount of labor that goes into making them both is the same. But if that clothing line is associated with a celebrity or lifestyle brand, it is deemed more valuable. Baudrillard called this “sign value,” which, he argues, subsumes both exchange value and use value to become the principal element of value in postmodern society.[44]

For Lyotard, Postman, Baudrillard, and other theorists in this vein, late capitalism and present-day media pose distinct challenges that require further analysis beyond what prior modern philosophies can provide. People receive and process information and consume in a way unlike any point in history, and this shift warrants further reflection.

Postmodernism Is a Condition, Not a Prescription

Contrary to how they are often portrayed by both the left and the right, postmodern theorists rarely prescribed a positive guideline for action. Rather, most of the key theorists analyzed the contemporary condition, and they were quite concerned about their conclusions. And just like in modernism, postmodernism contains a variety of ideas, and they do not necessarily form a unified theory. Postmodernism is frequently referred to derogatorily, as if it is a kind of bad philosophy. But this accusation is not only vague, but makes an is/ought error. The postmodern theorists were mainly concerned with describing the current condition of the world, not telling people how to act. They were analyzers of a world that had changed significantly, in all aspects of art, culture, politics, and economics. Hence, when the term “postmodernism” is invoked, its conjurers should clarify what is meant by it, as the term is loaded with a variety of meanings. Even the definitions presented here are simplified versions of much more complex ideas. The postmodern theorists have some keen insights to the world today, but they require a bit more engagement with their ideas than is usually given to them.

Footnotes:

[1] Michel Foucault, “Critical Theory/Intellectual History,” in Critique and Power: Recasting the Foucault/Habermas Debate, ed. Michael Kelly (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994), 124.

[2] Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos (Ontario: Penguin Random House, 2018), xviii, 302, 306; Jordan Peterson, “Postmodernism: Definition and Critique (with a Few Comments on Its Relationship with Marxism),” Jordan Peterson, May 25, 2018.

[3] Allan Bloom, “Our Listless Universities,” The National Review, December 10, 1982, 29.

[4] Roger Kimball, “The Grooves of Ignorance,” The New York Times, April 5, 1987, 7; Roger Kimball, “The Treason of the Intellectuals and The Undoing of Thought,” The New Criterion, December 1992.

[5] Jeet Heer, “America’s First Postmodern President,” The New Republic, July 8, 2017.

[6] Ryan Cooper, “Republicans Have Become Their Own Caricature of Postmodernism,” The Week, December 18, 2018.

[7] Modris Eksteins, Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing, 1989), xv.

[8] Peter Childs, Modernism (London: Routledge, 2008), 46–55.

[9] H. James Birx, “Nietzsche and Evolution,” Philosophy Now, October 2000.

[10] Karl Marx, “Letter to Ferdinand Lassalle in Berlin,” January 16, 1861, in Marx/Engels Collected Works, vol. 41 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1931), 245; Ian Angus, “Marx and Engels…and Darwin?” International Socialist Review, May 2009.

[11] Tim Armstrong, Modernism: A Cultural History (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010), 73–74.

[12] Peter Gay, Modernism: The Lure of Heresy (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 46.

[13] Ibid., 103–219; Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane, Modernism: A Guide to European Literature, 1890–1930 (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 191–292; Richard Taruskin, Music in the Early Twentieth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 1–4.

[14] Childs, Modernism, 20–21; Gay, Modernism, 142.

[15] Pericles Lewis, The Cambridge Introduction to Modernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 1–26.

[16] Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in Dialectic of Enlightenment (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2007), 94–136; Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (London: Continuum Books, 1997), 313.

[17] Kevin Passmore, “Poststructuralism and History,” in Writing History: Theory and Practice, edited by Stefan Berger, Heiko Feldner, and Kevin Passmore (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 121.

[18] When the term “modern” is invoked in this context, it refers to modernism or modernist, not the colloquial use of the word to mean “contemporary.”

[19] E. H. Gombrich, The Story of Art (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1984), 470–479.

[20] Childs, Modernism, 80–107.

[21] Peter Watson, The Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001), 470, 515.

[22] Irving Sandler, Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s (Milton Park: Routledge, 2018), 2–12.

[23] These exact statements by Warhol may be apocryphal, but they are widely attributed to him and do represent his general views on art. For more insight on Andy Warhol, see generally: Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner Books, 1989); Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing, 1975).

[24] Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” New Left Review 146, no. 1 (1984): 65.

[25] Ibid., 55.

[26] Arthur Danto, “The End of Art,” in The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 110–111.

[27] “Paris,” Absolutely Fabulous, dir. Bob Spiers (London: BBC One, 2001), television.

[28] Simon Gunn, History and Cultural Theory (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2006), 21–22.

[29] Anna Green and Kathleen Troup, “The Challenge of Post-Structuralism,” in The Houses of History: A Critical Reader in History and Theory (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 289–300.

[30] Nicholas Royle, Jacques Derrida (London: Routledge, 2003), 23–25. See also: Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Spivak (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), passim.

[31] Ibid., 92–93.

[32] Ibid., 62–63.

[33] Sara Mills, Michel Foucault (London: Routledge, 2003), 53–66. See also: Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge: And the Discourse on Language (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), 21–78.

[34] Ibid., 97–108; Green and Troup, “The Challenge of Post-Structuralism,” 302. See also: Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (New York: Random House, 1965), passim.

[35] A post-industrial society is one in which the service industry generates more wealth than the manufacturing sector, a society composed less of producers and more of consumers. This economic trend has continued since the late 1960s.

[36] Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (New York: Penguin Books, 1985), 107–108.

[37] Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984, originally published in 1979), 6–8, 37.

[38] Caitlin Johnson, “Cutting Through Advertising Clutter,” CBS Sunday Morning, September 17, 2006; Louise Story, “Anywhere the Eye Can See, It’s Now Likely to See an Ad,” The New York Times, January 15, 2007, A1.

[39] Jean Baudrillard, America (London: Verso Books, 1988), 27.

[40] Jean Baudrillard, “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place,” in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, trans. Paul Patton (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 61–87.

[41] Richard Lane, Jean Baudrillard (Milton Park: Routledge, 2009), 81 – 98. See also: Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994, orig. 1981), passim.

[42] The Matrix, dir. Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski (Burbank: Warner Bros. Entertainment, 1999), film.

[43] Aude Lancelin and Jean Baudrillard, “The Matrix Decoded: Le Nouvel Observateur Interview with Jean Baudrillard,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies 1, no. 2 (2004): 1–4.

[44] Lane, Jean Baudrillard, 71–75. See also: Jean Baudrillard, For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (Candor: Telos Press Publishing, 1981), passim.

By Shalon van Tine