CHARLES DARWIN—On His "The Origin of Species"

by Budd Titlow

Text excerpted from book: “PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change” written by Budd Titlow and Mariah Tinger and published by Prometheus Books. Photo credit: Copyright Shutterstock (2).

Almost everyone who has studied science, and many of those in other fields of study, know that Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution became the foundation of modern evolutionary studies. What is not so well known is that maybe no scientist in the history of the world suffered more scorn and ridicule than Darwin did after he completed his quintessential research and finally published his monumental 1859 book "On the Origin of Species". Waiting more than twenty years before finally going public with his earth-shaking findings, Darwin likened writing "Origin" to confessing to committing a murder.

Born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England, in 1809, Charles Darwin loved to be outdoors enjoying nature almost before he could walk. He enrolled in Edinburgh University with the goal of following his father’s and grandfather’s famous footsteps into medicine. There, Darwin learned that the brutality of surgery and the sight of blood turned his stomach—not especially good qualities for someone in the medical profession in those days. But university did enhance young Charles’s knowledge of science, a discipline that perfectly suited his love of the outdoors and his adventurous personality.

During a brief period, Darwin also thought about becoming an Anglican pastor and studied religion—but mostly botany—under the tutelage of Reverend John Stevens Henslow. Intrigued by his protégé’s keen interest in the outside world, Henslow suggested that Darwin take a position as naturalist on an expedition commanded by Captain Robert Fitzroy aboard a rebuilt brig quaintly named the HMS Beagle.

Darwin had always dreamed of traveling the world, and, though Captain Fitzroy had offered to cover his accommodations in return for his services as a naturalist, Darwin insisted on paying a fair share of the meal expenses. Little could anyone have imagined at the time that the pairing of Charles Darwin and the Beagle would live on in history as the boy and the ship that would shock the world and forever alter the science of human history.

Casting off under damp and dreary skies but not particularly rough seas, the Beagle—with a crew of seventy-three men, including young untested Charles Darwin—sailed out of Plymouth Harbor on the morning of December 27, 1831. Becoming seasick almost immediately—a malady that would curse nearly all his days at sea—Darwin started to have second thoughts about being on the voyage.

In 1835—after almost four years of exploring the world’s oceans—the Beagle reached the Galapagos Islands, one of Earth’s most remote and least explored archipelagos. This, of course, was right in Darwin’s wheelhouse, and he bounded ashore at each stop with an unbridled exuberance for making new discoveries—a little like telling a child he could keep whatever he found in a gigantic toy store. One of Darwin’s fondest memories in the Galapagos was hopping on top of a giant tortoise and trying to keep his balance as the gentle reptile lumbered through hillsides covered with volcanic rubble.

Returning home in 1836 after nearly five years at sea, Darwin turned his meticulously crafted notes into a book entitled The Voyage of the Beagle. Still in print today, this colorfully written book, infused with occasional flashes of wit and humor, perfectly captures the essence of the Beagle’s voyage and Darwin’s onboard adventures.

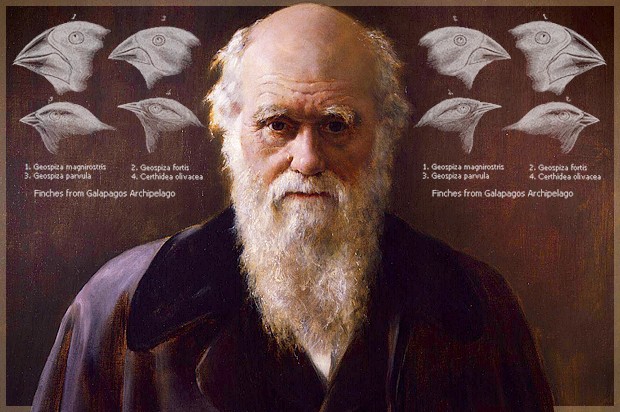

Darwin crystallized his theories about evolution while observing the genetically isolated populations of animals living on the Galapagos Islands. He was especially intrigued by the finches (actually part of the tanager family) that he found colonizing each separate island. Prior to his time on the Beagle, several mentors shaped Darwin’s budding theories on evolution. Jean Baptiste Lamarck planted, in Charles’ head, the notion that humans evolved from a lower species via adaptations. The two men differed in their view of how these adaptations came to be: Lamarck hypothesized that they happened during an individual’s life while Darwin postulated that nascent adaptations led to successful reproduction and species survival. Thomas Malthus’ studies on population economics led to Darwin’s idea of “survival of the fittest”, in which the species most well adapted outcompeted other species for limited resources. And, notably, Charles’ grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, shared many views about evolution with Charles, and eventually the public, first in poetry form and later in a book about speciation.

After arriving back home and studying his collected bird specimens with the help of a few professional ornithologists, Darwin noticed that each island’s finch population had a beak that was a different size and shape than that of the finches on the other islands. Moreover, the beaks of each isolated finch population appeared specially adapted to the different food species found on its island.

How could this happen, Darwin wondered? In his mind, the only explanation was that the finches on each island had evolved beaks that were best suited to eating the food that was most available on that island and were thus being naturally selected to reproduce. Darwin’s paramount publication, where he combined many of the aforementioned theories with his studies on the Beagle, was to come later—much later, in fact. Fearing for his reputation and in some cases his life, Darwin kept the radical evolutionary notions that were continually floating through his brain a secret. While his finches formed a substantial part of the backbone for his theory of natural selection, Darwin was not anywhere near ready to go to publication with his ideas in 1839.

Many explanations have been proposed to identify Darwin's reasons for waiting so long to come forward with his evolutionary theory. Some believed he was working on several other publications, and he never liked to start a new book before completing the ones on which he was already working. Others suggested that he was waiting for other scientists to produce findings that would help verify his beliefs. In general, a large portion of the population thought Darwin was worried that he would be ostracized by the Anglican Church and ridiculed by his friends and family.

We suspect that the twenty-year delay in the publication of Origin was a combination of all these factors. In fact, after receiving supporting research from fellow scientists Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Lyell in 1858, Darwin finally decided to finish his research and publish "On the Origin of the Species" in 1859 and the resulting worldwide debate began in earnest.

At first, Darwin’s beliefs that animals and humans shared a common ancestor shocked the Anglican Church and Victorian society to the core. By the time of his death in 1882, however, Darwin’s evolutionary imagery had spread through all of literature, science, and politics. Although professedly an agnostic, Darwin and his evolutionary theory were finally vindicated when he was buried in London’s Westminster Abbey—the ultimate British accolade.

It is not the most intellectual or the strongest species that survives, but the species that survives is the one that is able to adapt to or adjust best to the changing environment in which it finds itself. —Charles Darwin

So what can an earnest climate scientist learn from studying the life of past environmental hero Charles Darwin? First, Darwin had the gumption and stamina to stand by what he believed in his heart and mind to be true. Then he steadfastly maintained these beliefs and worked diligently to prove their veracity, even when he knew it would subject him to a storm of professional ridicule and the loss of relationships with friends and even family. Finally—working through all his doubts and reservations—he published his controversial theories and then lived to see them widely accepted. Steadfastly standing firm in the face of withering criticism and proving what is not only true but is also right is one of the most strenuous tests of heroism on the planet.

Author’s bio: For the past 50 years, professional ecologist and conservationist Budd Titlow has used his pen and camera to capture the awe and wonders of our natural world. His goal has always been to inspire others to both appreciate and enjoy what he sees. Now he has one main question: Can we save humankind’s place — within nature’s beauty — before it’s too late? Budd’s two latest books are dedicated to answering this perplexing dilemma. “PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change”, a non-fiction book, examines whether we still have the environmental heroes among us — harking back to such past heroes as Audubon, Hemenway, Muir, Douglas, Leopold, Brower, Carson, and Meadows — needed to accomplish this goal. Next, using fact-filled and entertaining story-telling, his latest book — “COMING FULL CIRCLE: A Sweeping Saga of Conservation Stewardship Across America”— provides the answers we all seek and need. Having published five books, more than 500 photo-essays, and 5,000 photographs, Budd now lives with his music teacher wife, Debby, in San Diego, California.