Futurism: A Break From the Past

The Futurism movement emerged in the early 20th century as a radical departure from traditional artistic conventions.

Spearheaded by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti at the turn of the 20th century, the Futurism movement sought to break free from the past and embrace the dynamic energy of the future. Its aim was simple: break away from tradition, and celebrate modernity. To this day, Futurism remains a pivotal movement in the history of art, inspiring countless modern artists. Here are six things to know about Futurism:

1. The Futurist Manifesto

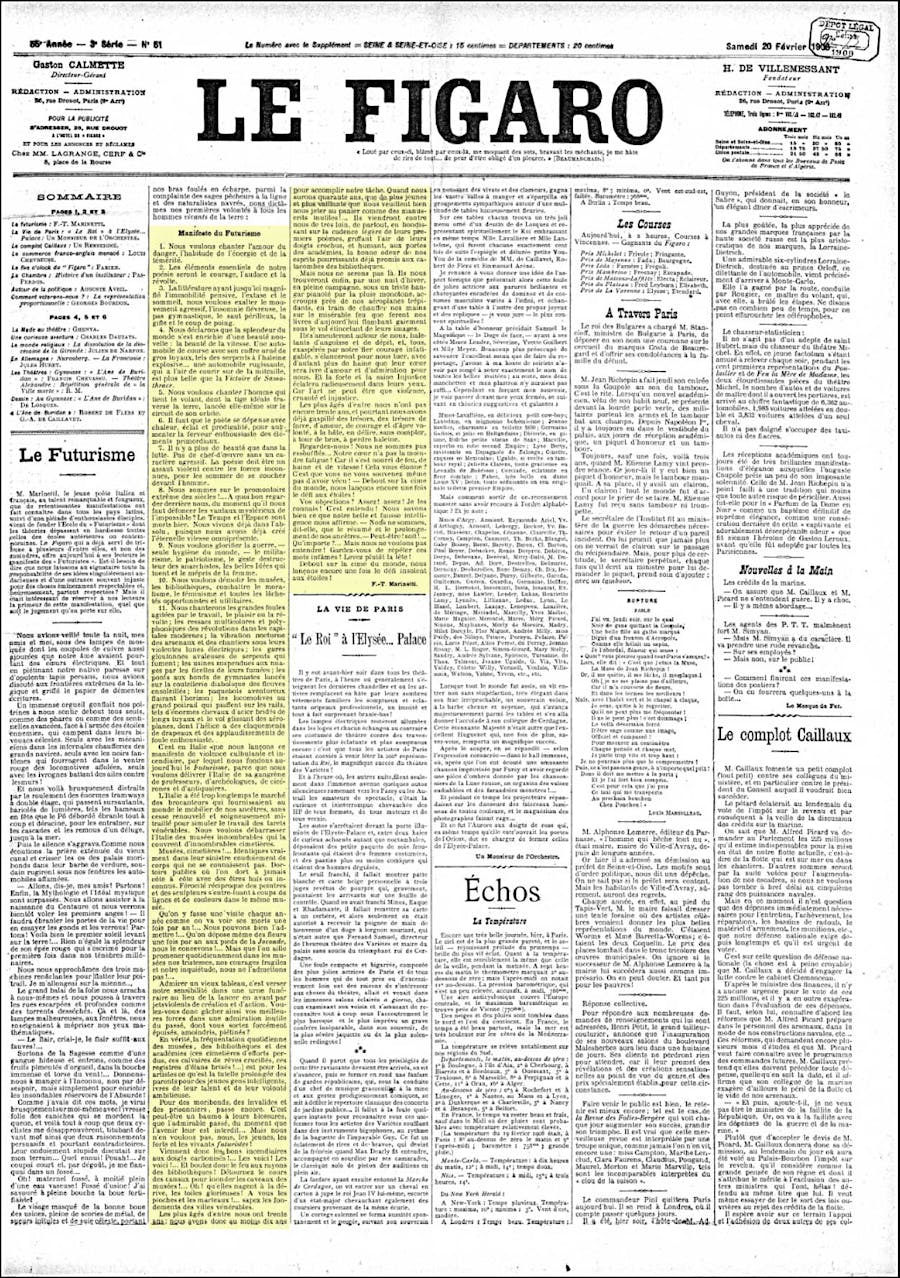

In February 1909, Marinetti penned the influential Manifesto of Futurism, first published in La Gazzetta dell’Emilia, and then translated in the French newspaper Le Figaro. In the manifesto, Marinetti argued for a need for change by vehemently repudiating traditional values and institutions in order to shape a new Italy. For him, this meant embracing innovation and the modern world of industry and technology. The Manifesto thus proclaimed the virtues of speed, violence, and technology while rejecting the nostalgia and romanticism of previous generations and their art.

Want more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox? Subscribe to our free newsletter!

Marinetti declared that the goal of Futurism was to 'free Italy from her innumerable museums which cover her like countless cemeteries.' Of the past, he wrote, 'we want no part of it.' Soon after its publication, Marinetti was joined by Italian painters Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini and Luigi Russolo, who quickly became advocates of the movement and published their own manifestos on art and culture.

2. Futurist Painting

Futurist painters, inspired by Marinetti’s manifesto, sought to capture the vitality and motion of the modern world by discarding traditional techniques and figurative traditions to embrace new forms of expression. The Futurists concentrated on movement, by which they aimed to convey the essence of a rapidly changing society.

Inspired by the Cubist movement, artists like Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini depicted dynamic scenes, fragmented forms, and abstracted perspectives. Through intersecting surfaces and spatial repetitions, they found a visual expression for the dynamics of movement, speed, and change.

See also: How Cubism Changed the World

See also: Eadweard Muybridge: A Pioneer in Art and Science

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912), by Giacomo Balla, is one of the most famous examples of Futurist painting where the legs, tails and ears of a dachshund are blurred and multiplied so as to create the effect of rapid motion. The painting illustrates the principles outlined in The Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto (1910) by Umberto Boccioni: 'On account of the persistency of an image upon the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves; their form changes like rapid vibrations, in their mad career. Thus a running horse has not four legs, but twenty, and their movements are triangular.'

3. Futurist Sculpture

Futurist sculpture similarly aimed to liberate art from its static nature and infuse it with a sense of dynamism. Umberto Boccioni, one of its most famous exponents, sought to portray the dynamic communion between object and space. In his most famous work titled Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), a human figure is shaped out of multiple planes through which the figure moves, as opposed to one solid static form.

See also: 10 Famous Sculptures in Art History

Other Futurist sculptors experimented with unconventional materials, such as glass, metal, and even electricity, to convey movement and energy. By merging sculpture with technology, they challenged the viewer's perception of form and space.

4. Futurist Architecture

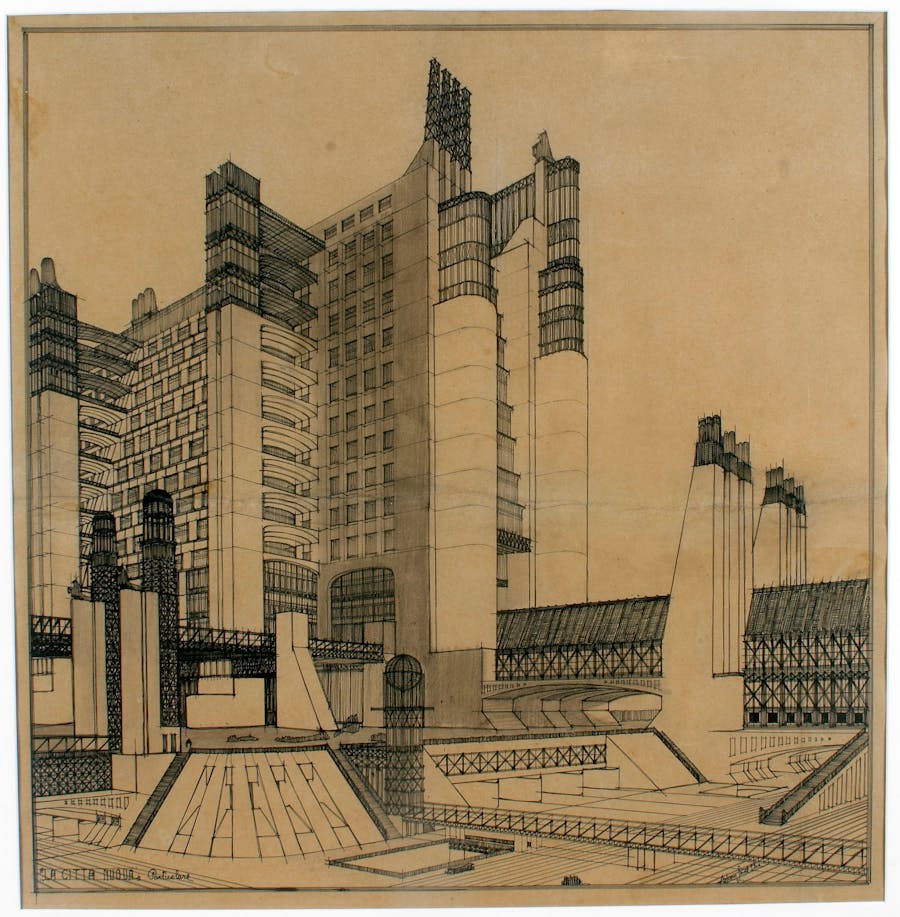

Futurist architects envisioned a new world that embodied the spirit of the industrial age. Architects like Antonio Sant'Elia and Mario Chiattone proposed bold futuristic designs that embraced the principles of functionality, speed, and efficiency. Antonio Sant’Elia, who wrote a Futurist manifesto on architecture in 1914, envisioned mechanised cities populated by industrial designs that rejected the ornamental excesses of the past.

See also: Bauhaus: A New Guild of Craftsmen

His drawings for La Città Nuova ('The New City') (1912–1914) sketch a modern, stripped-down city which favours simple and sculptural buildings to Baroque curves and decorations. The visionary sketches and manifestos of the Futurists paved the way for the development of modernist architecture, greatly influencing later movements such as Art Deco and Bauhaus.

5. Futurist Literature

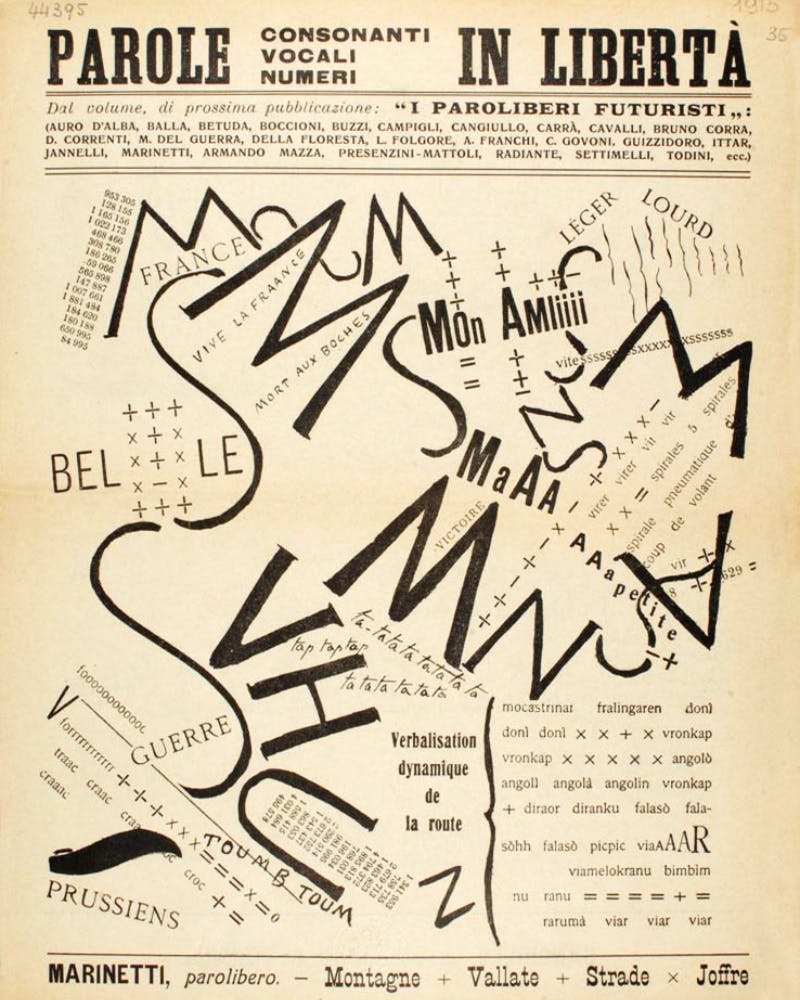

Futurist literature, much like its artistic counterparts, rejected conventional norms. Marinetti, along with other prominent Futurist writers, sought to capture the essence of the modern age by utilising fragmented syntax, onomatopoeia, and unconventional typographic arrangements to create a dynamic and evocative reading experience.

The Futurists established new genres in literature, most famously the parole in libertà, known as free-word poetry. This involved mathematical signs, a lack of punctuation and the absence of adjectives and verbs. Manifesto leaflets, posters, and literary collages were used to disseminate these new literary concepts.

6. Russian Futurism

While the Futurist movement originated in Italy, it quickly spread and found resonance in various parts of the world. Russian Futurism emerged as a distinct and vibrant branch, heavily influenced by the political and social climate of the time. Figures like Vladimir Mayakovsky and Velimir Khlebnikov sought to revolutionise not only art but also society itself through their works. Russian Futurism encompassed a wide range of artistic expressions, including poetry, painting, theatre, and even music. It celebrated the dynamism of the Russian Revolution and called for the creation of a new world order.

See also: The 15 Most Expensive Female Artists

In art, the main style adopted was that of Cubo-Futurism, seen for example in the paintings of Natalia Goncharova, which combined Cubist forms with Futurist subjects.

Developments and Legacy

The Futurists held their first exhibition outside of Italy at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery in Paris in 1912, and it featured works by Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Giacomo Balla. But already by 1914, only 5 years after the publication of Marinetti's manifesto, tensions between the group started to arise. Carlo Carrà, Ardengo Soffici and Giovanni Papini decided to formally withdraw from the group which they thought was too dominated by Marinetti and Boccioni.

From the birth of the group, violence, patriotism and anti-feminism had been central principles endorsed by the Futurists, whose manifesto declared that 'We will glorify war—the world's only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.' In 1914, the group started to campaign against the Austro-Hungarian empire. When Italy entered WWI, many Futurists enlisted in the army and engaged actively in militaristic propaganda. By the outbreak of the war, Italian Futurism started to dissipate.

In the 1920s and 30s, many of the Italian Futurists left supported Fascism in the hope of creating a new modern state. Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party in 1918, which was then absorbed into Mussolini's Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, making Marinetti one of the first members of the Italian Fascist Party. He later withdraw from the Fascist Congress but supported the movement until his death in 1944.

See also: 1925: The Height of Art Deco

Futurism as an organised movement died out with Marinetti, but its style influenced many later movements, including Art Deco, Vorticism, Constructivism, Surrealism and Dada. Its ideals also pervaded much of contemporary culture, from Ridley Scott's cult-classic Blade Runner (1982), which openly references Sant'Elia's designs, to Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto's album Futurista (1986), also inspired by the movement and featuring a speech from Marinetti.