In academic circles, a word that is inescapable when discussing Renaissance art is paragone. Paragone translated from Italian, generally means “comparison” and this theme of comparison was the backbone for much of the Italian Renaissance. Paragone was a major topic of debate during the early modern period, pitting artists, philosophers, and humanists against one another as they discussed the merits of differing topics. Whether is was the paragone between different arts like painting and sculpture, different fields like painting and poetry, or the comparison between different artists, artists and patrons relied heavily on comparison to fuel the development of art.

The core of paragone was competition. Whether it was artists competing or different arts competing with one another, the Renaissance was fueled by this on-going competition. Perhaps one of the largest competitions during the Renaissance period was between Michelangelo and Raphael. Both working around the same time, the two were frequently in direct competition and comparison with one another. At nearly the same time Michelangelo was finishing his Sistine Chapel, Raphael was selected to paint a series of four nearby reception rooms with frescos, including his famous “The School of Athens.” Additionally, Raphael was commissioned to design a series of tapestries which covered the lower walls of the Sistine Chapel, directly below Michelangelo’s work. The two were, and still are, constantly compared and discussions of their style, how they influenced one another, and the pros and cons of each artist carried on even after the artists’ deaths. Raphael encouraged this comparison, often borrowing Michelangelo’s style to juxtapose his own. In Raphael’s Fire in the Borgo (1514), located in one of the Vatican reception rooms, he poked fun at Michelangelo’s style and parodied the older artists overly muscular figures on the left side of the painting while showing his own softer style on the right. Raphael was showing the public that he could paint anything, that while Raphael could do Michelangelo’s style, Michelangelo could not do his.

Beyond competition between artists, painters were working to distinguish themselves from other artists. Prior to the Renaissance, most painters were considered within the same class as artisans and craftspeople. Throughout the Renaissance, painters worked to elevate themselves beyond this status and show that painting should be considered amongst the esteemed and educated liberal arts, like poetry and literature. By comparing and placing painting in competition with poetry and other arts, they could elevate themselves. Painters desired to be viewed as educated and wanted their art to be considered similarly. Leonardo was one of the largest proponents of this, systematically comparing painting to poetry, mathematics, architecture, and much more. In his notebook, he wrote:

“If you historiographers or poets or mathematicians, had not seen things with your eyes, badly would you be able to refer to them through your writings. Poet, if you were to figure a narrative as if painting with your pen, the painter with his brush would more easily make it satisfying and less tedious to comprehend. If you claim that painting [is] mute poetry, the painter could say that poetry [is] blind painting. Now consider which is the more damaging monstrosity, to be blind or to be mute. If the poet, like the painter, is free in his inventions, [the poet’s] fictions are not as satisfying to men as paintings [are]. For, while poetry extends to the figuration of forms, actions, and place in words, the painter is moved by the real similitudes of forms to counterfeit these forms. Now consider which is a closer examination of man, his name or his similitude? The name for man varies in different lands, and the form is mutated only by death. And if the poet acts through the senses by way of the ear, the painter [does so] by way of the more worthy sense of the eye.”

-Translation in Claire J. Farago, Leonardo da Vinci’s Paragone: A Critical Interpretation with a New Edition of the Text in Codex Urbinas, Brill Studies in Intellectual History (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1992), pp. 209–11.

He argues that poetry and literature can only create reality through words and can never achieve the level of reality provided by painting and its ability to reproduce what the eye sees. For this reason, he argues, painting is superior to poetry and other liberal arts. This was further illustrated as artists began drawing influence from poetry, creating visual representations of classic poems and mythology from antiquity. Works, such as Titian’s Poesies, or “Poetry” series, brought poetry to life in a way Leonardo argued mere words could not.

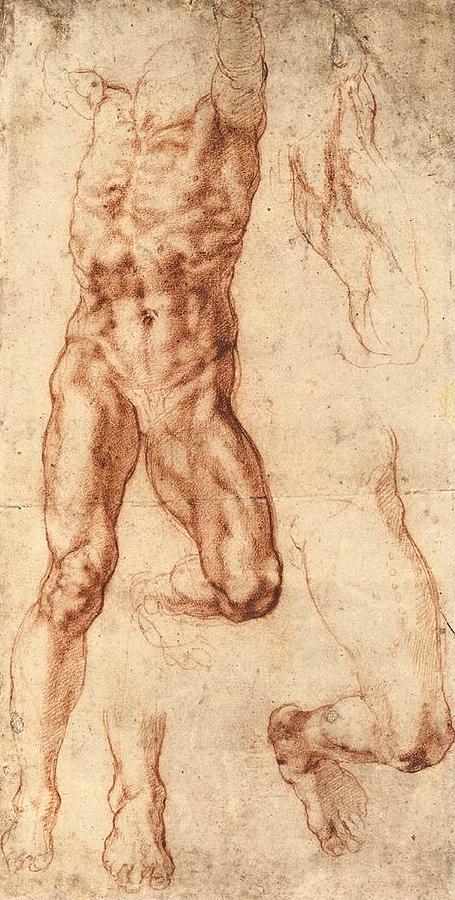

The last major paragone during the Renaissance was between the two major centers of art, Florence vs. Venice or disegno (design) vs. colore (color). Disegno was focused on the use of defined lines and shapes while colore used color to define shapes and figures and the lines were more fluid. The two were shown best in the work of Michelangelo (disegno) and Titian (colore).

Michelangelo was well-known for his meticulous design and the color added to his paintings served to emphasize the design. Outlines around the figures are more defined. The emphasis on design in Florence was in part due to it’s foundations, both in fresco painting (which did not flourish in Venice due to the damp climate) which needed strong design first and the creation of the Accademia di Disegno (the Academy of Design), which brought painters, sculptors and architects all under the theme of design. In Venice, as in the works of Titian, the emphasis was placed on the color and the light. Brushstrokes were looser, often described as “rushed” and many viewed Venetian paintings as unfinished because of their quick and more visible brushstrokes. The placement of color over design placed greater emphasis on light and movement. The debate between these two styles played out throughout Italy, captured in the treatises on painting by Venetians Paolo Pino and Ludovico Dolce. The divide and debate between these two came finally together in the work of Tintoretto, who dedicated himself to utilizing both. Throughout his studio, he included the inscription “Il disegno di Michelangelo ed il colorito di Tiziano” (the Design of Michelangelo and the Color of Titian).

Themes of paragone continue today throughout art history classes as students are asked to compare two paintings or argue for the superiority of one artist over another. Museums, much like Renaissance patrons did, encourage paragone as works by differing artists are placed next to one another, asking the viewer to view both and compare what they see. Comparison and with it, competition, is at the heart of Renaissance art and art history. It is how we understand innovation, influence, and so much more.

The next time you visit a museum, look at two paintings placed next to one another and step back. What do you see between the two? What is the same? What is different? What does these similarities and differences tell us about the painting, the artist, or the time period they were made in?

-Claire Sandberg

Resources:

Paul Hills, “Chapter 9: The Triumph of Tone and Macchia” in Venetian Colour: Marble, Mosaic, Painting and Glass.

P. Reilly, “Raphael’s Fire in the Borgo and the Italian Pictorial Vernacular,” 308-325.

Sydney J. Freedberg, “Disegno versus colore in Florentine and Venetian Painting of the Cinquecento,” in Florence and Venice: Comparisons and Relations (Florence, 1980): 309-322.