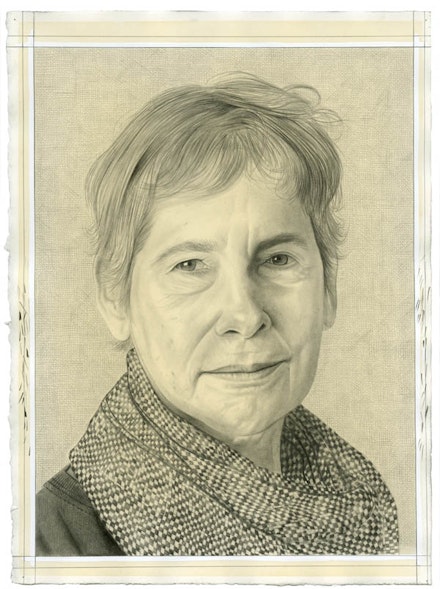

Art In Conversation

SYLVIA PLIMACK MANGOLD with Alex Bacon

Sylvia Plimack Mangold met up with Alex Bacon in New York City to speak about the threads that link together various periods of her career. A survey of works on paper by both Syliva and her husband, fellow artist Robert Mangold, is being presented at Annemarie Verna Galerie in Zurich, through May 24. Here in New York, on June 3, her work will be on view as part of a group show at Alexander and Bonin,and from June 9 through September 14, the National Academy Museum will present a selection of her paintings.

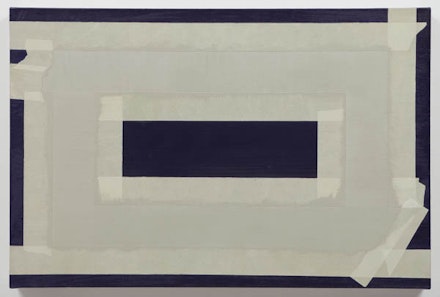

Alex Bacon (Rail): How did you come to the idea of incorporating tape at the edge of certain works of the 1970s?

Sylvia Plimack Mangold: I started using tapes to edit the composition within the picture plane. The first painting that had tape on it was a painting called “My Studio Wall.” It was a painting of tools I used: my rulers, my tapes hanging on the wall, etc. It was like a still life of tapes. Then I started thinking about using tape, not as a depicted object in the work, but as part of the process—measuring and taping—and so I began making paintings about measuring and taping. And of course I used real tape to make the image of the painted tape, so it all got very Baroque. I like that because it seemed open ended. I could save all these tapes I was painting and see where they overlapped, and that began to get me thinking about transparency and how tape changed color. For example, if it was over a yellow it was one color; if it was over dark blue it became green.

Rail: So there were a lot of different possibilities that came out of something so seemingly simple as painting tape, and maybe precisely because it was so simple—like you said the layering of color, luminosity, etc.—those issues became very clear when you got down to something so elemental.

Plimack Mangold: It’s not like I had it in my head. I just thought, “Oh! Look what I did! Maybe I can do this.” And also I found out that the tapes would set up a foreground, so it didn’t matter how I painted the landscape, because landscape is just something out there, and I could play with that. And since the painted image of paper and tape was so precise, the landscape could be about brushwork. But everything I did was contrived, I knew exactly what I was doing. Now I don’t, even though I’m painting directly from nature, especially the trees around my home upstate. And I find it much more difficult, more challenging. Even though in other ways it’s simpler, since it’s a simpler mind state, I just have to keep my place. Which branch was I looking at? And get the space of the tree, which you have to deal with. Perspective, and then you experience having to see it, like Cézanne, exactly like Cézanne. And that’s where I am now.

Rail: It’s an interesting journey in a way, because most people would imagine that you would go in reverse. That you would start with the tree.

Plimack Mangold: Like Mondrian.

Rail: Right. So I think that’s very interesting and significant that, in a way, for several decades you were investigating the terms and the materials of painting, and the possibilities of what can happen on that flat plane, in a not dissimilar way than, say, the Minimalists, or the Conceptual artists. Do you feel that perhaps, in that long investigation, you learned certain things that made it possible to go back and look again directly, and not have to have any mediation? As in the tree paintings you have been making for a while now. For many previous years, taped borders served as a mediation of the painted image of landscapes.

Plimack Mangold: I feel like I don’t have devices anymore.

Rail: Right. Because there is no tape, it’s just the tree now.

Plimack Mangold: It’s just the tree. And I think I would have never taken on painting a tree like I do now when I was younger because it really is hard. And you might think it’s an accomplishment to paint a ruler or a piece of tape or anything that’s flat, but it isn’t. If you want someone to get satisfied, take a piece of wood and try to paint it. It’s not hard. But if you’re trying to make a painting that’s really interesting in terms of how the paint comes together to form the image, to me that is very hard. It should be so that there’s a balance, so that the image isn’t stronger than the paint, but the space should be overall. I read your interview with Bob [Mangold], and he wonders why it takes me so long [laughs], and that’s why.

Rail: That’s interesting because that sounds like a Cézannian problem, right? Like Cézanne is looking at Mont Sainte-Victoire, for example, and he’s wondering, “how do I convey my felt experience of my distance from the mountain?” Then, in each of your paintings of trees there is a similar evocation of felt distance that seems simultaneously extended and collapsed.

PlimackMangold: That’s the tension in the painting. That’s what holds you looking, and that’s the creative part of it, and I must say I don’t know how it happens. It happens in the frustration, and in the focus and the engagement. It’s not like I have a system.

Rail: Do you find that you’re constantly reworking your paintings to get them to come together, as Cézanne felt he had to in his paintings? The empty patches in many of the later paintings are where he couldn’t resolve the pictorial system he had established in a given work. He thought that when he put something there, everything he did would then set off the balance, and it was this long process of working over the canvas until it all cohered. And sometimes they wouldn’t so he would leave parts of it blank.

Plimack Mangold: Sometimes those spaces are resting places. They’re very important. There’s always also the problem of the seasons changing. But I started off doing winter paintings.

Rail: I was going to say—often your trees are quite bare.

Plimack Mangold: Well it was a long time before I could figure out how to actually paint each leaf, because leaves are so high in a tree, you can’t really see them as separate little shapes. So with the maple tree that is right outside my window, some of the limbs come right up close to your vision, so I can see each one. And that’s been in the last five to seven years.

Rail: So in a way your paintings are changing as the tree is growing.

Plimack Mangold: That and me. I just didn’t think I could paint each leaf and figure out exactly how to make it work. Because leaves are like camouflage, so where are they coming from? You can’t see the limbs, the branches. You want to paint the growth—the way they grow and fall on each other. Well, now in a way I have figured out how to do that.

Rail: That’s interesting because you were talking about perspective, and I’m more aware of it in the earlier work, in the floors or the mirrors. While in the later paintings of trees you often seem to crop the field in certain ways, avoiding the use of perspective too much.

Plimack Mangold: Yeah I don’t want a horizon, because a horizon seems to be a pictorial space. And if you take the horizon out, then the space is more like that of a cloud-filled sky, or of a field that is going up, coming in close, or over you.

Rail: So almost like a kind of dome space, is that what you’re after?

Plimack Mangold: Well not dome, but thrust, in terms of the tree paintings. However, in the nighttime landscape paintings I would say that, yes, I saw the sky as a dome.

Rail: A kind of up and over movement? That’s a lot to try to accomplish in painting, because you’re dealing with a rectangular object that addresses its beholder frontally.

Plimack Mangold: Well I don’t know any other way. I don’t know any other medium that would do it, except maybe video. And not even video because it’s still flat. All those mediums are flat. And the thing about painting is you have this real tactile material to which you can make all these adjustments. I don’t know, maybe photographers can.

Rail: I completely agree with you. Again, it’s that Cezannian problem: how would you convey, in photography or video or whatever, that sense of felt rather than logical visual distance? The camera eye is a machine of sorts that transcribes a certain understanding of space. In a way the camera eye is the perspective lens, it’s even more perspectival than our own vision, which is binocular, so we’re trying to reconcile two images into one, but the camera lens can have that classic Renaissance innovation, one point perspective. So, again, that sense of distance that we feel is precisely about vision’s inherent eccentricities and inaccuracies. How we feel in relation to an object, versus what we think we see, is what is exciting about moving around in the world. For example, that sense of changing perspective is why we want to be in nature. So it makes sense to me that you privilege painting, because painting can both hold those different variables together, and keep them in play in parallel way to how nature creates those variables in the first place, organically and inherently.

Plimack Mangold: Because you can change the surface. You can make it a dry, rough surface. You can scrape it down to the canvas or you can build it up. No matter what, with photography it’s always the same: made up of little spots. Painting is made up of many different kinds of marks and even if you put different kinds of marks in a photograph, it still feels the same. There are limits and advantages to every medium. I don’t know why I love painting so much. I can certainly never imagine myself as a sculptor, or as a photographer.

Rail: You have a desire to play with questions of surface and tactility, and to create these kinds of sensations within the work, which aren’t possible outside of painting. I mean for me personally, I’m not a painter, but as an art historian, critic, or as a curator, I find myself not exclusively, but mostly, drawn to painting precisely because of that intimacy and that sense of connection and that sense of variability. Paintings seem to have lives; they change.

Plimack Mangold: Right, it’s chemistry. It’s alive and it does change.

Rail: Having said that, I wonder was that something you felt even early on, when you were doing more reduced or conceptual paintings? In the sense that you were not, as you said, dealing with a kind of live subject matter which could generate those kinds of experiences. But what were the kinds of experiences that led you to paint those kinds of images, the rulers and the tape, and so on?

Plimack Mangold: Well those paintings were autobiographical, the idea of deception, illusionism being deception, and the difference between fiction and reality.

Rail: That’s interesting because, in the ’60s dogma against certain kinds of illusionism—whether you were [Clement] Greenberg or you were Donald Judd—those similar reasons you just gave for wantingto paint illusionistically were precisely why many others felt all kinds of illusionism had to be mitigated or defeated. So, for example, Greenberg and Judd had very different ideas of how that should be accomplished, but they share the idea that if someone just presents the same old perspectival model of pictorial space, even if it was fully abstract, then it was still deceiving the eye. For someone like Judd, especially, this then took on larger connotations of an almost moral deception, and so on. But they seem maybe to be two sides of the same thing. If you’re aware of what ends illusionism can be put to. Your paintings, for example, put forward the terms of that deception and that illusion—lay them bare.

Plimack Mangold: Getting rid of illusionism was also my reason for wanting to do it. But I didn’t know I was doing it. Because when I painted floors I was trying to create this plane in space, and create a grid that I could put a chair or something on to help me locate these objects in space in a realistic way. And then I found, I had these chairs on the floor and I took the chairs away because I found that I had gotten really involved in painting the floorboards. When we moved to the Catskills in 1971 I found this old mirror and I thought, “Oh! I don’t have to paint a gymnasium if I want to make bigger paintings.” I could take the mirror and put it in and then I have the floor, and then the floor and the mirror. And I really didn’t realize what I was setting up for myself with mirrors. So I did a mirror painting called “Absent Image” because I didn’t want to paint myself in the mirror. It wasn’t about portraiture, but it in a sense it was, by “absenting” myself. And then I thought about, if you put the mirror in this corner and then you could see that corner, that’s an interesting idea about “in-corners” and “out-corners.”

Rail: So you like corners a lot.

Plimack Mangold: Yes, I like corners. Well, I didn’t think about corners that much, but I found a way for them to signify an idea. For me, corners seem to be able to potentially suggest a lot of things. Then I did all the mirror paintings, and then I just got to a certain point where I did a floor painting with corners, but it was a horizontal painting and the floorboard went one way, instead of another way. So that’s why I put a ruler on the floor, to show it coming forward. I think that was the first floor painting I did. Then, when I did that I said, “I can paint tools,” and so I painted my studio walls. You would think I planned this whole journey, but I didn’t. I remember when I had my mirror show, it was at the Fischbach Gallery, and Mel Bochner came up to me, and he started going on about all that I had done with all these mirror paintings and I thought to myself, “Did I do all of that?” [Laughs.]

Rail: So people making Minimal and Conceptual art liked your work?

Plimack Mangold: Yes, Carl Andre wanted me to do a portrait of one of his floor pieces.

Rail: Bob [Mangold] told me that you said no. Why did you say no?

Plimack Mangold: Well, the material didn’t interest me.

Rail: You liked the floor itself, but not his sculptures?

Plimack Mangold: I liked his sculpture, but I didn’t want to paint it.

Rail: As you have said, in a way, if it’s portraiture, it’s not actually about the subject being represented, but maybe the absence. Those early paintings seem to be almost an investigation of your personal, even domestic, but also professional space, insofar as you are an artist painting your studio and tools of the trade. For me viewing them, it’s not a sense of your absence, but I feel that when I look at these paintings I might be stepping next to you, like we are looking together. I am seeing from your perspective. I may not literally be in your perspective, but I am next to you, as if you are showing me something. Like we sat down and really looked at the floor of your house together. It’s not a casual, “and here’s a room,” gesture. Right? Rather, it’s an intense investigation of, “well, what is the nature of this space?” It really is philosophical.

Plimack Mangold: And if I put a figure or a something in one of the paintings it would fill the space, and you couldn’t enter it. The most abstract paintings that I probably ever did were those tape paintings. There were narratives in them of the process of painting the tape. Those were fun paintings to do.

Rail: Oh, they were?

Plimack Mangold: Yes. They were freeing for me, it was like playing with the medium, putting a lot of oil or varnish, to play with the shiny surfaces. Sometimes I’d show the tape, the real tape that used to be there, and it could be matte. So then I would paint this shinier, mirror-like blue around the tape before I took it off, so you’d see just a shadow of the tape. You could just try all these different things, leaving clues about what was there, what was removed, and what was still there. It got very complicated, but I didn’t mind, it was a break from looking at real life. Those were done out of my head. It was the closest to not looking at life that I ever came. Not looking at something outside of the studio.

Rail: Even though, ironically, those are the most, in a way, concrete paintings, right? In the sense that they’re just the tape, or just the ruler.

Plimack Mangold: That’s right. I try to not have anything I don’t need in those paintings. And I do try to not overdo something. I want it to be something to experience completely as a whole. If I look at something, and it seems to jump out at me, I remove it.

Rail: You were saying earlier that you felt that the act of painting for you was a kind of escape, or that you were in a way, somehow out of the world when you were doing it. I wonder, is that a kind of experience that you want for the viewer even though they’re often looking at something of the world, whether it’s a tree or a floor?

Plimack Mangold: I would say that the experience I want the viewer to have is to enter the painting, and then come back to the surface.

Rail: And what’s at the surface?

Plimack Mangold: The actual material. I don’t want the viewer to get stuck in there.

Rail: So is that the kind of sense of space, even in the trees, a feeling of going into the world of the tree, and then coming back out?

Plimack Mangold: Traveling through the tree. I have tried very hard to get the relationships out of nature in the work, but then to bring you back to how it was painted, to the surface, and to go back and forth.

Rail: Which is why, perhaps, these paintings are more self-evidently painted, as were the landscapes, than the trompe-l’oeil effects of the floors and the mirrors.

Plimack Mangold: Well if I did trompe-l’oeil, I’d repaint over trompe-l’oeil. I mean especially with the tapes and the rulers. There was one painting I did where I had the rulers going off the edge, and then it was too self-contained, there was no exit. So I invented some reason to make an exit. I don’t even remember what it was, just a way to get out.

Rail: How does a viewer imaginatively enter a ruler painting?

Plimack Mangold: Well, that’s a whole series of propositions I set up for myself, I think. But I did some works on paper where I said, “Okay, an 18-inch ruler the size of a 12-inch ruler if it’s one inch diminished.” I don’t even remember. Like, if you diminished a 12-inch ruler, an 18-inch ruler, okay 18 inches, and then we go back, and then instead of making an 18-inch ruler, I would make it a 12-inch ruler. Or I would measure, like the one that’s at MoMA, which is called “36 by 36,” that canvas is 30 by 36, so it’s a 36 inch ruler, diminishing. And when it diminishes, it’s 30 inches.

Rail: You’re really playing with this question of illusionism and, again, it seems to come out of that moment in art history when people were trying to investigate, “what does it mean to exist in a particular kind of space?” That investigation of not only what does it mean to experience an object or whatever in space, but also what does it mean to then translate that into art, whether you’re Donald Judd making a plexiglas and steel object, or you’re you, painting one of your paintings, there’s still that questioning of your idea of space and perception and what is actually perceived. Those two things are placed alongside one another, and that becomes the interest of the work, in very different ways, but I think they’re related. You’re playing with that sense of perception.

Plimack Mangold: It seemed boring to just paint it the way it looked. Just to make it look real? That’s not enough.

Rail: Because what does that even mean? What is that act you’re engaged in—even if that was the idea. I think you must have just thought, “well, what am I even doing when I’m painting?” Right? There’s some translation, so why not make that translation active? The tools of that translation, even, are the subject of the painting.

Plimack Mangold: That’s right, that’s right! But I even took it further, to what it couldn’t be. Just because it seemed right, if you’re an artist, you try to do something that’s sort of contradictory.

Rail: Where do you feel your work is at the moment?

Plimack Mangold: It’s changed very much from last year to this year because of the tree outside my studio window. I’m now looking at its very uppermost limbs and twigs. So instead of them having so much volume, instead you can see the sunlight on the branches. But I’m more interested in the bigger narrative, and in the relationship of all of these as they spread out. And then there’s a kind of fragileness because it’s winter. The branches are painted flat, but I don’t want them to read flat. So instead of a plane coming out of the floor, the plane is coming up. But all those lines have to have an organic connection to each other as they grow. I have to go out to see it, and my vision is not as good as I wish it would be, and I keep losing my place.

Rail: Do you think those aspects of your vision, and your ability to imaginatively move through the tree, inflects your painting of the tree?

Plimack Mangold: Yes. I would say so. It’s a kind of focus and meditation for me. If I go into my studio and I just work for an hour, I feel centered.